A riding hat is the most important item of riding equipment you will own. Georgia Guerin investigates how this vital bit of kit is tested

WHEN you look inside your riding helmet, or a helmet you might purchase in your local tack shop, it’ll have the information about what safety standards the helmet meets, along with marks of assured quality – or it should do if you’ve made a good purchasing decision. But if we’re honest, as riders, do we really know enough about what is our most important piece of protective kit? Have we chosen it because we’ve decided it’s safe as well as stylish?

Helmet safety standards can get a little confusing and appear to many as just a string of letters and numbers. Luckily, the UK is home to some of the most knowledgeable experts at the forefront of helmet design and they are dedicated to helping us make the best possible choice – and protecting our heads.

STANDARDS are in place to ensure that the helmets we buy provide us with a certain level of protection. Behind each standard is a technical committee of experts ranging from hat manufacturers and design engineers to traumatologists and surgeons. Claire Williams, executive director of the British Equestrian Trade Association (BETA), is involved with a number of these groups and committees and convenes the group responsible for European equestrian helmet standards independently of her role at BETA.

“As a group, we come together with the aim to make helmets safer. We are currently working on a new version of the EN1384, which will be more similar to the PAS015 product approval specification,” she says. “Once it has been republished, we can begin work on a full revision, which will include work from another group who are developing new tests that simulate the impact of a rotational fall. In terms of standards, this will happen soon – but in real-life terms, this will take a few years.

“When we’re developing a new standard, we have to consider what the consumer is willing to buy,” she adds. “Fifteen years ago, a ‘super-standard’ was introduced. Helmets designed to meet this standard were more similar in design to a motorcycle helmet, but this unsurprisingly wasn’t popular with equestrians, so the standard was withdrawn. We have to strike the balance of working for safety and finding something that riders want to wear.”

Claire, who also advises the FEI and a number of national equestrian federations, predicts that future standards will become more sport-relevant.

“We’re working on new tests and new headforms [metal “heads” used for testing] that will help us better simulate the effects of a rotational fall or crush injuries specific to equestrian sports.”

Matt Stewart, Charles Owen’s head of innovation, currently sits on committees responsible for VG1, EN1384, PAS015 and ASTM F1163.

“It’s a long process to introduce a new standard,” he says. “When we meet, we present research, discuss the data and make suggestions about how it can be improved. I am currently pushing for changes to existing standards as well as to make new ones.

“When the committee is in agreement about how to proceed, we can move forward with introducing an update to the standard. Once this is announced, manufacturers will have some time to ensure their hats are compliant and ready for sale.

THERE are several standards produced by different countries and each one requires helmets to undergo various tests that simulate potential accidents. In some tests, the helmets sit on headforms.

Helen Riley heads up the engineering team at Champion and sits on the committees chaired by Claire. She also acts as an advisor to the British Standards Institution, Snell Foundation and FEI. Helen explains that there are five main areas of testing – crush, penetration, shock absorption, harness strength and stability – and reveals that the tests include…

- Linear impact tests: “These aim to test your helmet in a variety of accident scenarios by dropping it onto an anvil from a height. A flat anvil is used to test even ground, while a hemisphere-shaped anvil is used to test impact more similar to an uneven road surface or motor vehicle. A hazard anvil, which has a sharp edge, simulates colliding with an object such as an arena fence or being caught by a hoof. The energy transferred to the headform is calculated in each instance and the helmet will fail if the threshold is exceeded.”

- Penetration test: “This simulates an impact from a sharp, pointed object, such as branches or a horse’s studs. The helmet is placed on a headform and a 3kg metal spike is dropped from a height – if the spike triggers a sensor on the headform, the helmet will fail the test.”

- Lateral deformation test: “This assesses the helmet’s ability to withstand varying degrees of crushing force. If the helmet deforms more than the maximum limit, it will fail.”

- Harness retention test: “This measures the strength of the harness and its ability to keep the helmet in place during and following an impact.”

- Stability tests: “There are two stability tests – the roll on/roll off test is passed if the helmet remains on the headform when weight is attached and then dropped from a height, while the other is passed if the helmet moves less than 15mm when force is applied by hand.”

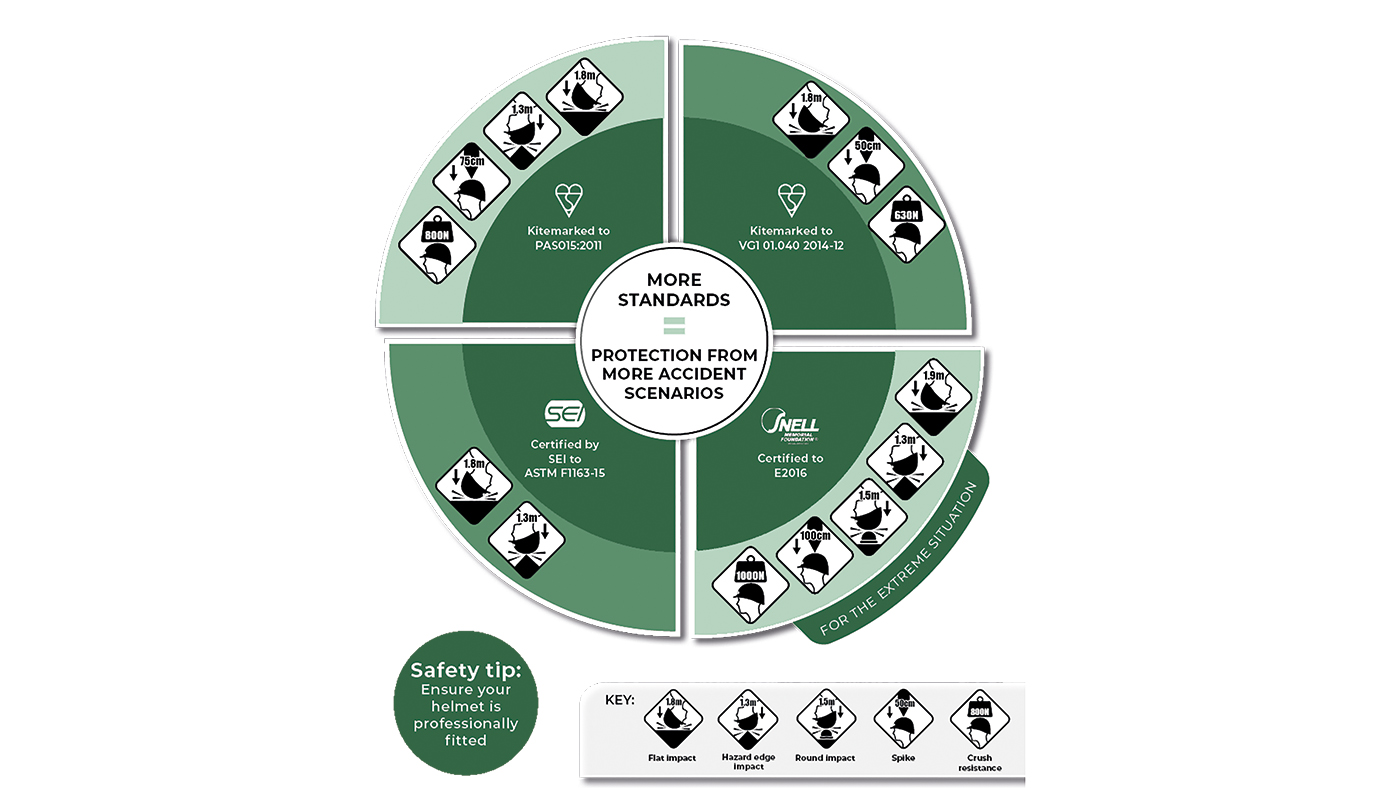

Each standard requires a different number of these tests to be undertaken and each one to varying degrees. Helen references the penetration test as an example – in this test, the higher the spike is dropped from, the more force it will hit the helmet with.

“VG1 requires the penetration spike to be dropped from 50cm, PAS015:2011 from 75cm and Snell E2016 from one metre, while ASTM F1163-15 does not include a penetration or crush test at all.”

Matt adds: “Each standard has its merits, but some are simply more robust and stringent than others. The best way to protect yourself is to choose a hat that meets multiple standards because it has been tested in the largest range of scenarios.”

Some manufacturers can test helmets in their own labs, which is where Matt spends most of his time working.

“When we develop a new design, we’ll first decide which standards we want a hat to meet. Then once we have a design, I’ll simulate the tests on a computer before physically testing all our prototypes,” he explains.

Although manufacturers may be in a position to test their hats, they can’t certify them and this is done independently.

“We are part of the BSI Kitemark scheme,” Matt adds, “so we send our hats to them for independent testing. This ensures that not only does the first hat produced meet the standard, but those that are produced the following year and beyond are of the same quality.”

Claire elaborates: “Being part of the Kitemark scheme proves that the manufacturer submits helmets for regular batch testing, is independently audited, and also uses approved suppliers and parts. It is normally required by your governing body or organisation’s hat rules.”

The most basic marking is the CE mark which, though not a quality mark, does show the product is fit for purpose as outlined in European personal protective equipment principles. Despite Brexit, Claire suggests you’re still likely to see CE marks on products for years to come.

“From the end of next year, new products will have to have a UKCA mark. Over time, this will replace the CE mark, but as EU member countries, such as Ireland, still require the CE mark, it’s likely that products will display both.”

CLAIRE explains the complicated system of standards with a simple analogy.

“Standards are like a cake recipe. You have raw ingredients, the measurements and the method. Your end result – the cake – is a hat that meets a standard. Each hat created by a different manufacturer looks different because its ingredients (different materials and technologies), method (different tests) and measurements (level of protection required by each test) are different to any other. But crucially, they still complete the recipe and produce a certified hat in the same way that you can make a cake in countless different ways. How the manufacturer gets to the finished product is up to them.”

Claire also points out that just because a hat is four times more expensive, it doesn’t make it four times better.

“It‘s like handbags – you can spend £50 or £5,000. While one might be designer and blingy, they are both up to the job of carrying your things. You have to choose the right hat for the job – standards will help you work this out – and it has to fit. The best hat in the world can’t do its job properly if it doesn’t fit.”

This feature is also available to read in this Thursday’s H&H magazine (1 April, 2021)

You might also like:

13 riding hats that are worth your attention

Trauma doctor shares simple life-saving actions all equestrians should know

Dr Diane Fisher spoke about the simple, potentially life-saving actions, people can take if a friend hits their head at

Advances in helmet testing should mean safety boost *H&H Plus*

What is MIPS technology and why could it revolutionise riding helmet design?

A safety feature, already widely used in cycling and skiing helmets and designed to reduce brain injuries, could revolutionise riding

Subscribe to Horse & Hound this spring for great savings

Horse & Hound magazine, out every Thursday, is packed with all the latest news and reports, as well as interviews, specials, nostalgia, vet and training advice. Find how you can enjoy the magazine delivered to your door every week, plus options to upgrade your subscription to access our online service that brings you breaking news and reports as well as other benefits.