What’s involved in rehydrating a sick horse or restoring the body’s natural fluid balance? Karen Coumbe MRCVS explains the importance of fluid therapy

Horses can be surprisingly reluctant to drink when you want them to.

Different methods have been developed to encourage them, from adding apple juice to the bucket or warming the water, to feeding supplementary salt or soaked hay and wet feed to up the water intake. Such tactics can help, but not when a horse is seriously unwell.

The amount of water a healthy horse needs to drink daily will vary, depending on factors including his age, environment, nutritional status, workload and temperament. Certainly, some will only want to drink out of their own buckets containing their usual tap water, in their own stable, so it is worth trying to accustom a horse to change before it is required.

On average, a healthy 500kg thoroughbred will drink approximately 12 to 40 litres of water per day. With one big bucket holding 10 litres, that means a lot of fluid to administer to any sick horse who is unable to drink – especially if he is losing additional fluids from bleeding, for example, or diarrhoea.

Fluid therapy can be life-saving for the sick horse and is crucial for treating conditions such as dehydration, shock and serious inflammatory responses.

In many colic cases, intravenous fluids are essential during surgery – or sometimes instead of surgery – as well as post-operatively. Fluids help to support a horse suffering from post-operative ileus (reduced or absent gut motility), which is an unfortunate complication of some colic surgery cases.

If the intestines are not functioning properly, quantities of fluid can pool in the stomach and elsewhere. Since horses cannot vomit, this results in the challenge of nasogastric reflux and the need to pass a nasogastric (stomach) tube to decompress the stomach and remove trapped fluid.

Catheter or tube?

Intravenous (IV) fluids work by rapidly boosting the circulatory system volume, hopefully helping recovery. Different fluids options are available, including whole blood, plasma and various types of saline.

A vet will administer IV fluids to a horse via an IV catheter, which is typically inserted into the jugular vein on the neck. Complications can arise, including venous injury with thrombosis or infection, causing a blockage. This is more likely to happen if a sharp-ended hypodermic needle is used to access the vein. It is better to use a purpose-designed catheter.

There is also a risk that air can enter and cause an embolism or blockage elsewhere in the horse’s circulation. More likely is that the catheter will come loose and slip out of the vein, resulting in fluid leakage and bleeding. It is essential that the horse is carefully monitored.

In some cases, it is simpler to administer fluids by the enteral (oral) route. This removes the need for sterile fluids and catheters, carries a low risk of infection and costs less.

In very sick patients, however, blood is diverted away from the gastrointestinal tract to the vital organs, limiting the absorption of fluids by this route. Serious colic cases will not tolerate fluids by mouth, and nasogastric intubation is not ideal for recumbent horses.

There are also potential complications with this method, including the rare chance that

a stomach tube may be misdirected so that fluids enter the lungs. A more common problem is that passing a stomach tube causes a nosebleed.

The general rule is that, ideally, a horse should drink water of his own accord. If he will not, fluids by stomach tube are the next best choice, in most cases, before IV fluids are considered.

Liquid assets

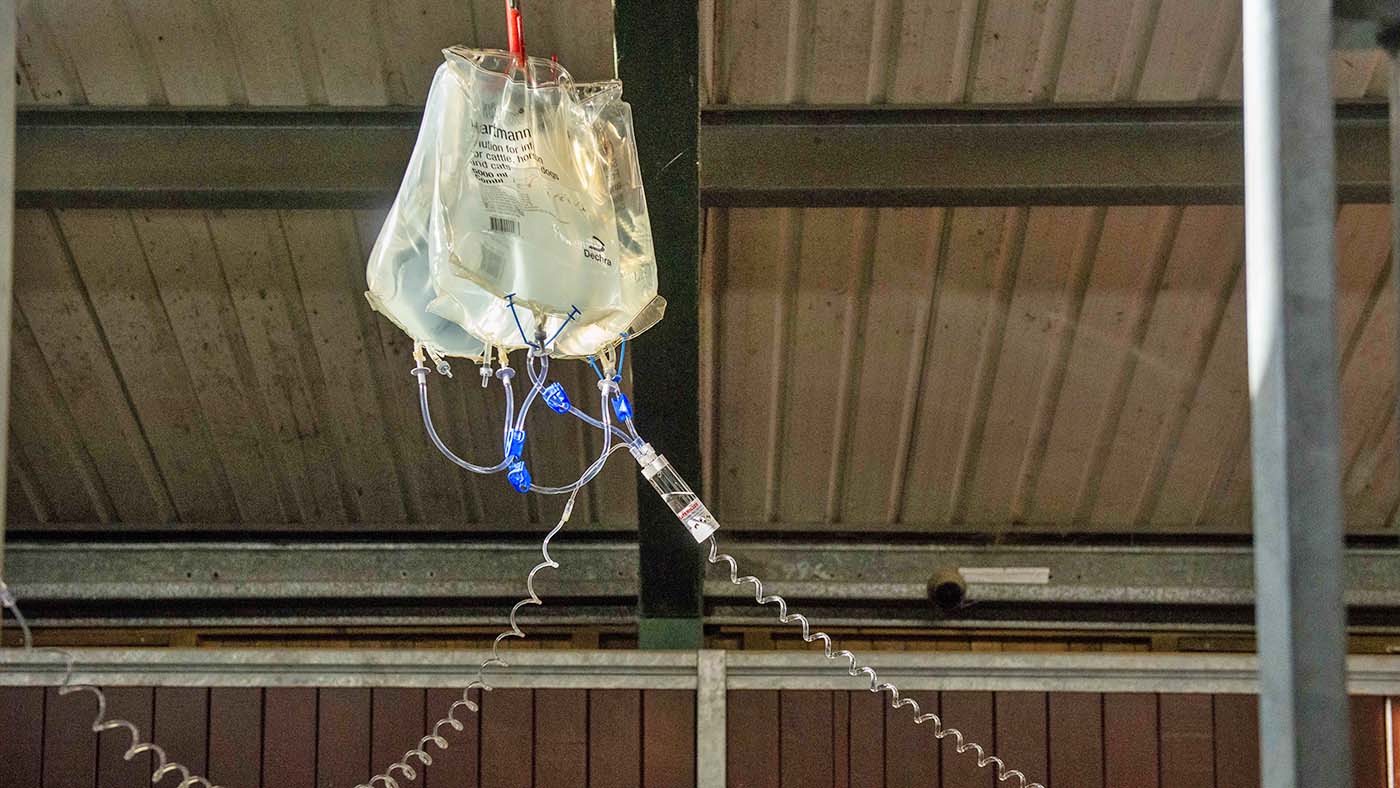

Whereas a human will receive tiny 250 to 500ml bags of intravenous sterile fluids, administered slowly, a horse will be given several huge five-litre bags. These larger bags are efficient and, when needs must, can be set up to hang from a beam in a stable or barn (pictured).

We are fortunate in this country that such large bags of sterile life-saving fluid are available for equine veterinary use. In some countries, only smaller bags can be obtained, making IV drip administration more difficult.

Recent studies have shown, however, that excessive fluid therapy might be more harmful than once thought. Strategies are being investigated to reduce fluid doses to optimise the level that is beneficial, which will also reduce costs.

This feature is also available to read in the Thursday 25 March issue of Horse & Hound magazine

You may also be interested in…

5 ways to keep your horse hydrated after competition

Dengie senior nutritionist Katie Williams gives some top tips to keep your horse healthy and hydrated after competition

Dehydration in horses can be deadly — here’s what you need to know

The dangers of overreach and strike injuries *H&H Plus*

Sharp contact between a hind hoof and a foreleg can cause significant injury, as Dr David Stack MRCVS explains

Modern breeding methods: what are they and which one is right for your mare?